MARCOS RAYA | THE ARTIST. Multifaceted artist Marcos Raya, a living legend in the Chicago cultural scene.

ARTIST, ACTIVIST, MURALIST and painter Marcos Raya was born in Guanajuato, Mexico in 1948. At age 15, in 1964, he moved to Chicago to be with his mother. Attempting to evade the Vietnam draft, Raya returned to Mexico in 1968 where he was involved in the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) student protests before relocating to the southwest community of Pilsen during the Civil Rights and Chicano movements of the late ’60s and ’70s.

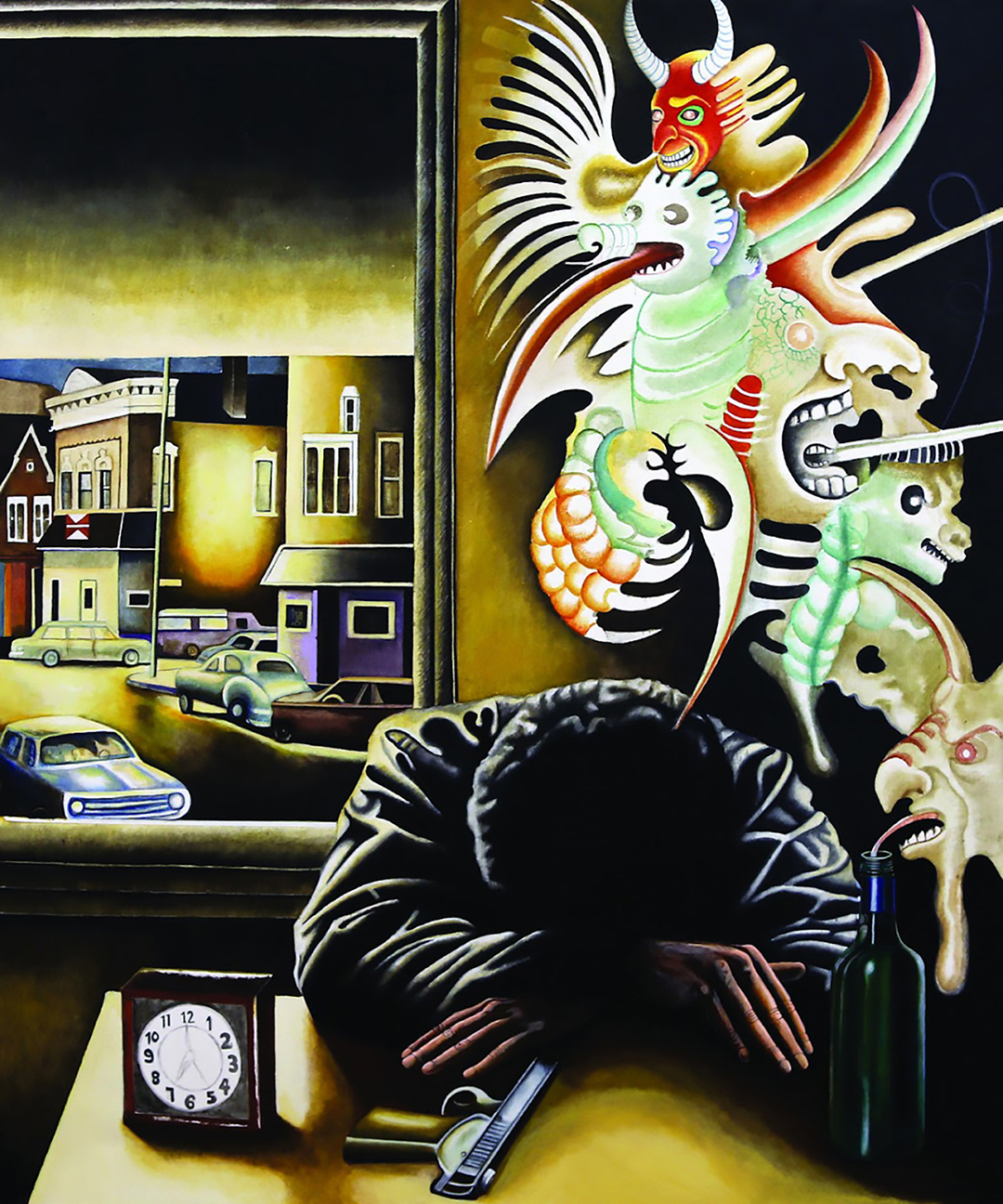

Raya began creating artwork that reflected his shared pain and anger caused by what he saw throughout the streets of his neighborhood. In his works such as “The Alley’’ (2010) and his self-portrait “3 A.M Sunday Morning” (2002) we get to see the inner turmoil and struggle against Raya’s personal and political demons that continues to lay rampant within the community.

Using his strong influences in Psychedelic Surrealism and Dadaism, Raya explores the sociological impacts of war, political disparity, and technology throughout his work, rejecting what he commonly calls Mexican Nationalist art.

What media do you work in? When did you know you were an artist? Tell me about the first time you created a painting.

I am an artist. The difference between Picasso and Matisse is that Matisse is the painter, Picasso is the artist. I am an artist.

Nowadays kids, you give them a couple of brushes and they doodle and that’s it. It’s not easy to become an artist. For me, art is a bunch of ideas that you put together. Art is politics, art is everything. So, in order for me to achieve that, I had to come to the conclusion that time doesn’t exist. In order for me to become an artist, I needed 24 hours to think and to paint. For that, one of your biggest obstacles is money, rent and food.

Raya sits back in his paint-stained chair and laughs, clutching a cane adorned in metal and skull imagery.

Not many people go to the extremes to not only be an original but be a full-time artist. I went out to gamble my life and became a full-time artist. That happened when my high school teacher told me to visit an art institute [in Massachusetts.]

Back then, in the early ’60s for you as a minority to say that you will become an artist, they would think you were crazy because there was no such thing. When we walked into the art class and I saw these students create beautiful things, I told myself, ‘This is what I wanted to do.’

“The difference between Picasso and Matisse is that Matisse is the painter, Picasso is the artist. I am an artist.”

As a man who has strong ties within political groups and movements, how do sociopolitical themes play into your art process? How has this evolved throughout your career?

I ended up in Mexico City in 1968 [where] there was a student movement. That’s when I got politicized and when I started to hate the Mexican government.

My perspective on life has changed drastically. Locally, when I first got to Pilsen, I noticed right away something was wrong because from one day to the other the neighborhood was filled with drugs and guns. It’s something else. When I arrived in Pilsen, it was a Chicano neighborhood, and there were a lot of Mexican families. But in the ’80s we had the Mexican exodus when everything became mexicanized. With that, some of the artists that came to Mexico, they are the ones who got all the projects. The problem with this is that they didn’t really tackle the identity, the real deal of what it is like to be a Mexican living in Chicago. Instead, they bring this nationalistic infant view of us as singing Mexicans, a character of Mexicans.

When my show opens, I assure you no one from Pilsen will show up. How am I supposed to talk to the young people? The sickness, what I call Mexican Nationalism, those kids who invade downtown with their Mexican flags. I find it disgusting because we forget that we live in a city where there are all kinds of people from all over the world, and not everyone does what Mexicans do. I have to say, I think it’s ignorance. I have to ask myself, ‘What happened to us?’ Nobody cares about what we do in Pilsen except those in that bubble. And I don’t think I’m welcome in that bubble.

How has your identity and cultural background played a factor in your artistic expression? Tell me about your experiences moving to Chicago in the midst of the civil rights and the Chicano movements.

Before we built our first Mexican neighborhood in Chicago we lived under the status quo, where everything was white and for whites only. And I remember how horrible that was. So to me, moving to Pilsen was like, ‘Let’s build Pilsen.’

I look back to what I did in the little studio at 17th St. and Halsted. One of the paintings that I did when I was only 17 years old, I saw it on PBS News Channel 11. It was showcased as one of the best paintings in the Chicano movement in the United States. It’s hanging right now in the New Museum in Houston. It shows even then I was doing really well, and I was interested in studio art, not the politics in the street. I had one foot in the street, one foot in the studio.

Murals, for me, were something pure. It was here in the streets, painting political murals, organizing the people to fight for a better living, and it worked. I never got paid for the six murals that I painted. What kept me strong was my ideas. I always enjoyed painting, I enjoyed writing books, I enjoyed the whole imaginary world of art. It’s remarkable because when I arrived in Pilsen it was considered to be one of the most violent neighborhoods in the United States. We had the war on drugs. The kids from back then in the ’70s, they grew up without leadership. So right away like any Latin American country, instead of joining the people to protect the neighborhood, they joined the enemy, the drug dealers. For about 30 years that neighborhood was run by gangs, there was a lot of killing. So, I have a few questions about identity, about imagery.

When I first arrived in Chicago, I was only fifteen. The first thing I noticed was the Chicanos and Black people being so violent against each other. I used to wonder, ‘Why?’ But then of course little by little I realized they were victims of society, of racism. From day one, I told myself I had to stay away from those people, that I had to find my own identity, and that’s what I did.

Raya rejects the common Aztec calendar themed murals we see decorating Pilsen’s walls today.

The history of Mexico is black. It still is. All of these colorful things come from the huevos, these Hispanic colorful fellas that like to party and drink tequila. Little by little we become cartoons of our own selves, by dressing like Frida and [Día] de los muertos is now a spectacle.

I understand you moved to the United States from Guanajuato in 1964. What were your reasons for the move and what has kept you in Chicago?

I guess it has to do with how we grew up. For instance, my mom lived in the same neighborhood on Taylor St. all her life. Maybe it’s that, the familiarity.

What do you think of the term Latinx to identify people of Latin American or Spanish background?

That word, ‘Hispanic,’ came back. We fought against it so hard. For instance, when a person organizes art shows, one of the biggest mistakes they make is, when they get money to get a “Hispanic” show or a “Latino” show, they put everyone in one bag. Usually, the only thing they have in common is the last name. There is no connection, there is no political message or identity.

Now, ‘Latino.’ There was a time in the ’60s we had a Latino thing going on on a continental level. Starting with the Latino boom, some of the best writers came out of it. There was also a sense of revolution, especially when it came to Cuba and the student movement and many things. Back then it was very political and radical, to be a Latino. With time, with everything else, things begin to get commercialized.

Because I refuse to be a citizen, I’m still very Mexican. I don’t say I’m a Mexican because I love my country, no. Being Mexican makes me feel like I’m a part of the universal Mexican family. When I paint, I don’t throw my Mexicanism in your face. I don’t do it. If I paint and some Mexicanism comes out, it has to be very natural, it has to come out of your soul.

Be First to Comment