“Shore|Lines,” a multimedia exhibit created by Regina Agu exploring the connections between Black North American migration, community memory, place and — most importantly — water, arrived at the Museum of Contemporary Photography in January 2025. Several News Reporting students wrote reviews of the art exhibit.

By Naomi Ashkenazy

Immersive panoramas, traditional photographs and archived footage present and document the significance, but common lack of recognition regarding stories and locations central to Black American migration and displacement.

Through life-sized landscapes of forgotten waterways, Agu’s “Shore|Lines” at the MoCP invites viewers to stand in spaces where important Black American histories unfolded.

The first space immediately transports viewers to Galveston, Texas, with vinyl sheets displaying an empty beach wrapping around half the room.

“The size of the piece puts you in this landscape in a really interesting way,” curatorial assistant and tour guide Judson Womack said.

Galveston was the last place in the United States to hear about the Emancipation Proclamation, inspiring Juneteenth.

The installation allows guests to feel and experience these environments in a way that isn’t possible with smaller photographs. Through it, Agu brings people to historic locations that have risked being forgotten or never known.

On the opposite wall, collages layer photos of Black communities near southern waterways before and after Hurricane Harvey. Overlapping these images brings a significance and focus to the “existence and nonexistence” of these locations, as placing them next to each other would have told a different narrative according to Womack.

“It’s kind of this futile act of preservation,” he said.

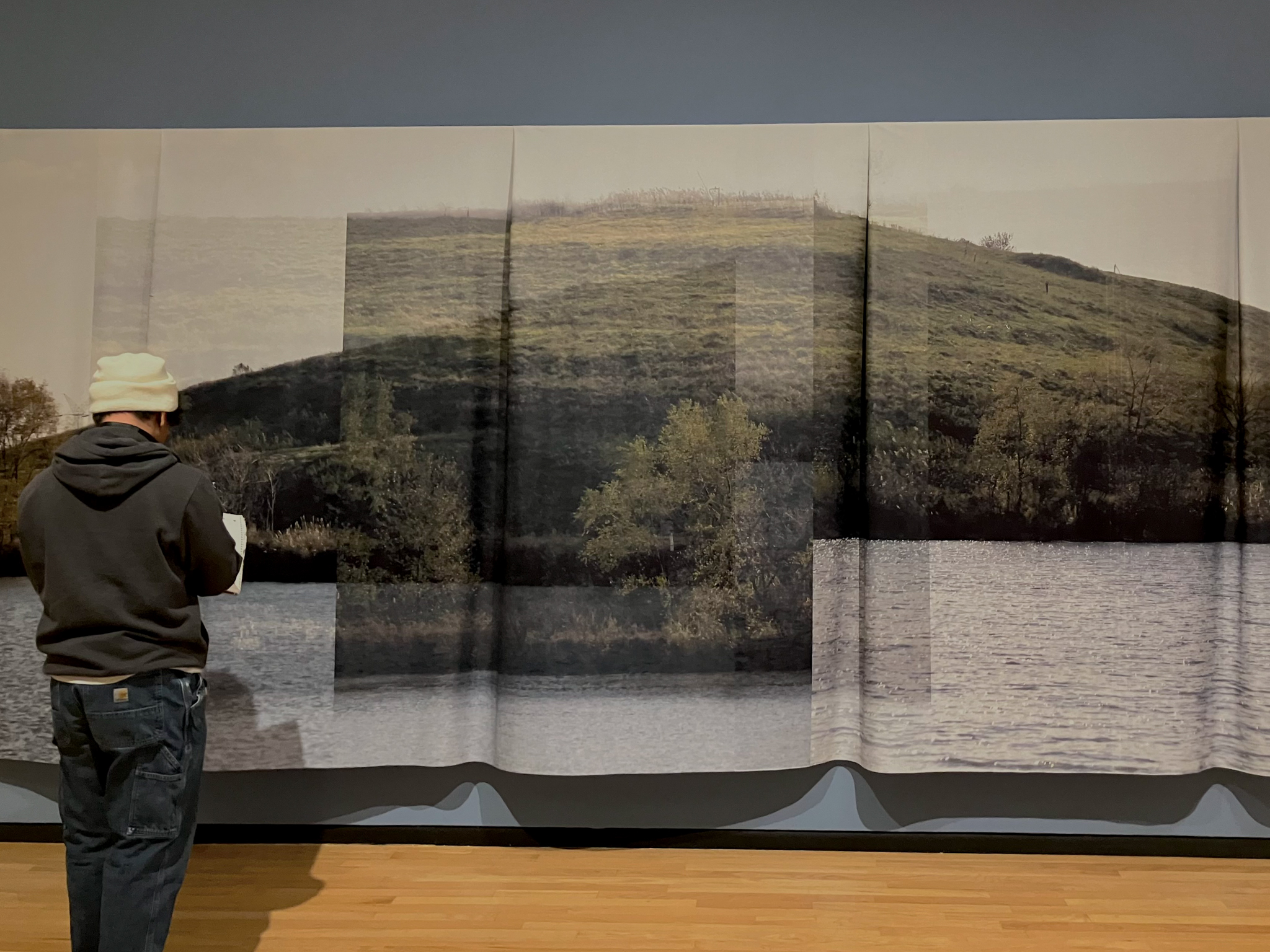

The second room continues the folded fabric motif and gives reference to the show’s theme of water, displaying landscape panoramas of Lake Michigan. The novelty of this second stage evokes a particular feeling for viewers.

“There is a sense that there is this journey to be had,” Womack said.

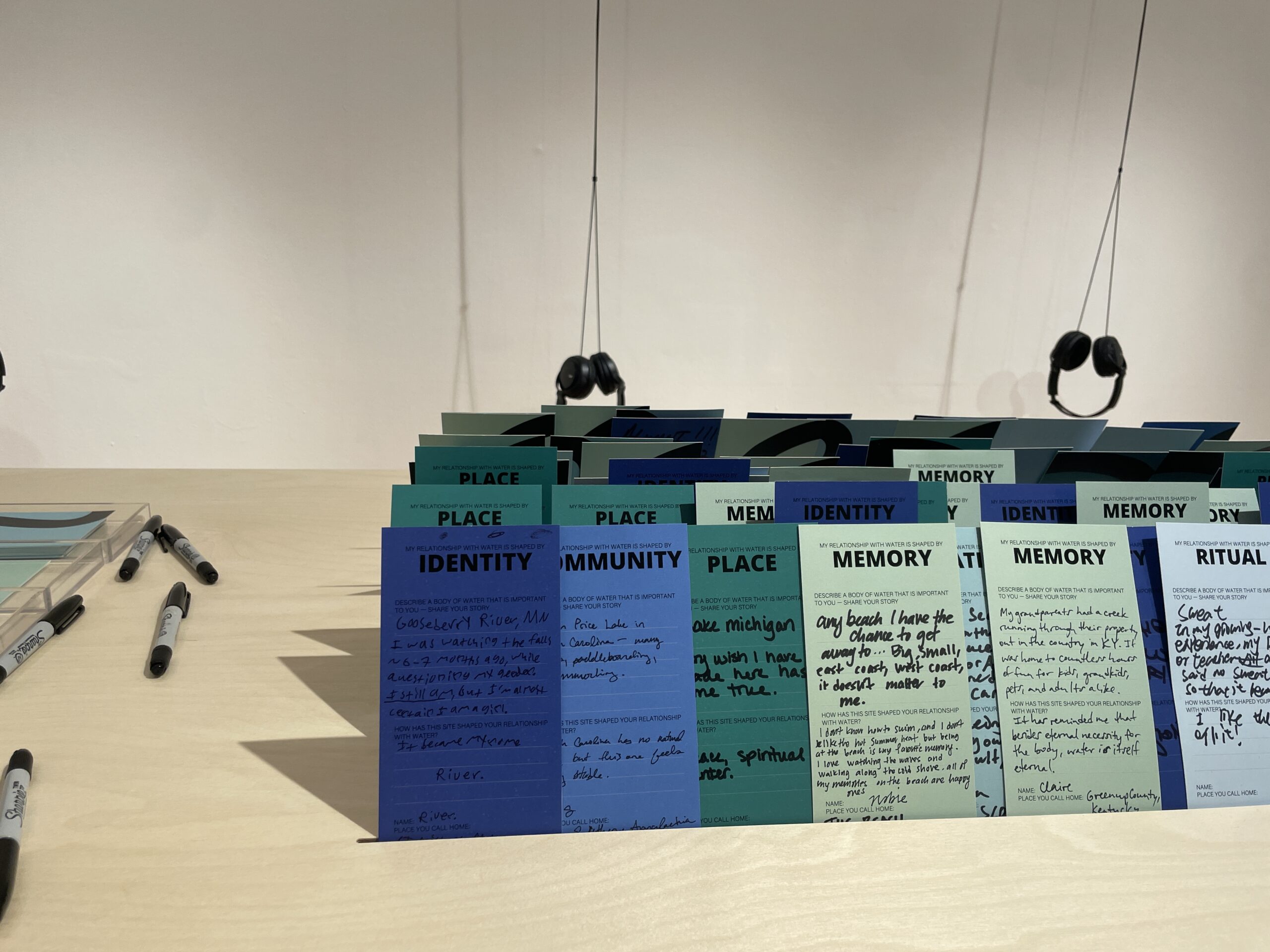

A separate interactive space designed by Akima Brackeen, assistant professor at UIC, invites visitors to write responses to prompts on color coded cards while listening to songs, interviews and oral histories about migration, memory and identity through headphones that hang from the ceiling.

The next floor houses Agu’s “field guide,” according to Womack. These smaller, traditional photographs help viewers zoom in on snapshots of the bigger picture of Black migration.

“When you make a piece small, it not only brings you in but it can also make it very intimate,” he said.

This co-archival collection deliberately excludes human subjects, directing attention to details depicting locations and the life and activity that was once there.

“Bywater 02, New Orleans” particularly stands out with bright, saturated colors, depicting an orange house with bright green plants casting shadows on sunlit panels. It’s a great example of how seemingly unexpected images can hold so much story.

“This house has people in it. Someone tends to these plants. Someone painted their house this color. This is the sunlight that shines on the people who live here,” Womack said.

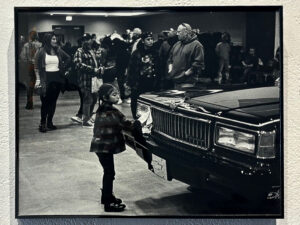

The last section features more co-archived photographs from MoCP’s collection and finally includes faces. We see Black families playing in and near waterways, people at work and in general having community experiences. According to Womack, Agu’s intentions with the exhibit was to “preserve a level of fragility but also a level of perseverance” that otherwise may not have been recognized or told.

By Miguel Loza-Sanchez

A tapestry coats the white walls from edge to edge. A beach, a perfectly blue sky, and varying pieces of evidence of life. It feels empty, despite it filling up half the room. But most notably, it’s a former plantation.

“Sea Change” is among the many pieces in Agu’s exhibit. The exhibit contains a collection of photos, all centered around bodies of water in relation to Black history and migration in the United States.

The most eye-catching part can be found on the first floor. The tapestries are panoramic, stretching out far as the eye can see — much like the lakes pictured in them. In stark contrast to “Sea Change,” the other panoramas’ subjects are water, specifically the coast of Lake Michigan. This, along with “Sea Change,” can be interpreted as the path taken by Black slaves on their way to freedom. It has a visual effect: the buildings shown on the coast are overlapped with water. They’re being submerged.

Agu’s exhibit has a running theme of livelihoods being affected by water. Some of her photographs are centered on the effects of Hurricane Harvey. “Garden” is one of them. It has two photos: a gate covered in a green net, and in the center, a slightly blurry picture of leaves. Womack said that the choice to embed both photos into the portrait reinforces the idea that these photos are coming from the same subject.

On the second floor, there are only portraits and landscapes, showing subjects ranging from waves, homes and foliage. Womack believes that this is meant to preserve the little things from these communities. The smaller portraits force the viewer to stop and take in the idea that these are real places with real people in them. Humanity is felt despite the lack of people as subjects.

The third floor of the exhibit is where humans are center stage. All the photographs in this section are not from Agu — rather, they come from the museum’s archives and were chosen by Agu. Subjects interact with Lake Michigan; playing in the water, working with water, and industrializing the water. In other words, the role humanity plays with water, specifically Black people, is common throughout this section. It helps put a face on who gets affected by the climate. Moreover, who experiences the joy these bodies of water have to offer, as Womack puts it.

By Llani Froeber

The “Shore|Lines” exhibit entrances visitors with landscapes where Chicago’s erratic lakeside waves crash against shores, contrasting with the endless sand dunes of Galveston, Texas. Stepping into this immersive experience, guests are encouraged to lose themselves in the world captured by Agu.

A focal point of this exhibit is the two large-scale panoramic installations on the first

floor of the show, stretching 174 feet in total and printed on billboard vinyl. Both pieces allow

guests to feel as if they are standing within the images.

Agu’s piece, “Edge, Bank, Shore” consists of various images of Chicago’s lakeside and riverside shorelines (Little Calumet River, Rainbow Beach, Lake Michigan) layered over one another. While the restlessness of the waves evokes a sense of presence, it is the intricate details provided by Agu that stand out. The billboard vinyl is billowy, with intentional folds that give the imagery movement, mirroring the waves themselves.

The use of folds to add character and motion to the flat photo is also present in Agu’s other large-scale panoramic landscape, “Sea Change.” This technique is most effective in the photograph of Galveston, Texas, and its man-made sand dunes. The folds make the piece more engaging to the eye rather than staring at a stagnant photo of sand.

Womack, also a MFA photography student at Columbia College Chicago, praised the technique. “It puts you in the landscape in a really interesting way,” he said. “Photography is all about solving problems; it’s meaningfully constrained.”

As a result of the artist’s effort to meaningfully connect with her audience, there was also an interactive activity room that held visitors’ attention.

Designed by Brackeen, six sets of headphones hanging from the ceiling each play a different playlist. The chosen music was selected to connect listeners to themes of water and its relationship to humans, exploring migration, memory, ritual, place, community and identity through sound.

“Being part of Regina Agu’s exploration of history and the connection between humans and water was truly impactful,” said Nevaeh Derkis, a Columbia College Chicago music business major.

“Shore|Lines” is a multisensory experience that resonates long after the visit ends, one where Agu creates an educational and thought provoking experience for visitors; inviting everyone to reflect on history and how the landscapes all around us have shaped us into who we are today.

By Anna Bitz

Water holds memory. In “Shore|Lines,” visitors are enveloped by water — vast, rippling images printed on vinyl tarps that wrap around the walls, immersing spectators in the fluid history of the Great Migration. The MoCP has curated the exhibit to allow visitors to explore sites where Black families once sought new beginnings, turning water into both a witness and a storyteller.

Agu’s overall work is based around historical representation, memory and Black geographies. These themes are carried into the works featured in this temporary exhibition. The photographs, though still, move subtly with the air, a layered effect crafted by the curators that enhances the sense of motion and investigation. These images are heavily depopulated, offering signs of life yet emphasizing absence — locations once central to historical moments now left empty.

Beyond the towering tarps, framed images ripple with memory, blurring past and present, movement and stillness. This is more than a photography exhibit; it’s an experience of migration itself — of landscapes left behind, of journeys both forced and free of history flowing ever forward. The places featured show remnants of lives once lived — homes people built, gardens tended and waters that provided both escape and sustenance.

Womack describes the exhibit as the “proximity of water that [Agu] has become attached to.” This attachment is evident throughout the three-floor exhibit, where Agu’s work transforms water into a vessel of both history and emotion.

The first floor, with art printed on billboard vinyl, introduces the elements of water and land. An interactive feature invites visitors to reflect on personal memories associated with water, allowing them to share and listen to others’ experiences while hearing the sounds of flowing water.

The second floor adds a sense of place and structure, with framed photos showing water adapted by human hands and industry. The third floor completes the exhibit with black-and-white images that align with Agu’s vision, incorporating people into the photographs. Agu hand-picked the pieces for this floor from the MoCP’s permanent collection. These subjects — captured in historical and contemporary settings — illustrate water’s role in industry, community and daily life, reinforcing the exhibition’s theme.

By weaving historical landscapes with personal connections, “Shore|Lines” transforms water into a powerful meditation on memory and migration. This exhibit is a must-see for those interested in history, art and the ways in which landscapes bear witness to human movement.

By Claire Gerald

As you stare out at the lake, a cool breeze blows and the waves begin to roll. But rather than the soft give of sand below your feet, there is the smooth polished wood of the gallery floor. You are not lakeside but standing in the MoCP in Chicago’s South Loop looking at billowing fabric panoramas on the wall.

The Lake Michigan landscapes and panoramic photos are a part of the “Shore|Lines” exhibit that is currently on view in the museum. Agu’s intent behind the project was to connect themes of Black culture through waterways and bodies of water.

Womack explains the exhibit as “an investigation of the land as it relates to Black history in America.”

Agu began working on the project in Houston, Texas ten years ago and continued to do so until the museum commissioned the exhibition.

Agu uses landscape, panoramic, fieldwork and documentary style photography to highlight places in the United States that are important to Black history. Her work engages with cultural moments and experiences such as the Underground Railroad, Juneteenth and the Great Migration. She uses techniques such as layering and collaging to create a forced perspective in her work.

In addition to her own work, the exhibit includes photos chosen by Agu from the museum’s

archives. These photos show the space of love, happiness and joy other Chicago photographers have also documented. Agu’s curation highlights these moments through experiences on the Chicago River and Lake Michigan, as well as in other ways of water in the city.

By Marc Balbarin

The word “photography” draws from the latin base of phōtós and graphé, translating into “drawing with light.”

For hundreds of years, the primary goal of many photographers was to transport a viewer into a space; sharing their perspective and putting the viewer in their shoes. Some may take this in a metaphorical sense; Agu however takes this literally, with her encompassing the viewer in her works.

Agu is a Chicago-based researcher and visual artist, who connects her field research with digital photography in order to examine locations of Black historical significance. This includes a forgotten plantation, former sites of the Underground Railroad and trail markers of the Great Migration along the Mississippi River. Agu documents the cultural significance of these locations, where the nuance is often hidden and forgotten by the people.

Throughout the first level of the exhibit, Agu fills the walls with large scale billboard vinyl prints. What makes this unique, however, is the various folds and drapes Agu employs in order to create natural depth upon viewing. This is complemented by air oscillating throughout the rooms, causing the curtains to waver and breathe life. “Edge, Bank, Shore” surrounds the viewer as they enter the exhibit, showcasing the Chicago lakefront and riverside through several composite images. In an adjacent room, “Sea Change” encompasses it with a wide panorama of the historical sands of 2016 Galveston, Texas. The powerful scale of the 80ft print surrounds the viewer, allowing for one to be transported onto the artificial sands of the location.

The second level of the exhibit offers what Agu refers to as a “field guide” to the South and Midwest, showcasing various framed inkjet prints of the landscapes. Despite her photos focusing on the environment, this does not mean a human element is missing from it. One such photo that embodies this is “Bywater 02,” which shows greenery both in front and behind a fence alongside a Bywater house in 2019 New Orleans. This photo could be interpreted as a metaphor for freedom from bondage, as its location was home to a former slave plantation. A photo Lake Shore Drive in 2021 demonstrates an intersection between the artificial and natural parts of our environment.

By Malik Gamble

A panoramic view of the beaches of Galveston, Texas, is the only appropriate place to begin the exhibit. The wraparound tapestry dominates half the room, depicting the dull sand dunes, pale blue sky and outcroppings of shrubbery of the beach. There is no water in the image. It is barren, as if it’s a desert. In 1865, the last slaves in the United States were freed in Galveston; their liberation served as the basis for Juneteenth. Yet, by the tapestry, you wouldn’t know that. There’s nothing there.

Nothingness lies at the heart of Agu’s “Shore|Lines” exhibit, which is a photographic exploration of Black migration through the waterways of America. The exhibition runs south to north, from the shores of Galveston to Chicago, depicting the landscape of these waterways and life along them. “Shore|Lines” is a showcase of the still-very-present issue of Black representation in a historical sense, though Agu explores this through the lens of the physical world that we occupy. For most of the exhibit, there is nothing within the photos themselves to suggest the historical importance of these sites to Black people and a wider American populace. To the naked eye, they are unimportant.

This is absolutely true for the first two levels of the exhibition. There’s nothing to ever truly latch onto in any of the images. Not even people. Traces of people are still there — in the occasional silhouette or the structures that line the waters — but you never truly see anybody. No faces are present in any of the photographs. A plaque says Hurricane Katrina is to blame for massive displacement of Black families, though only the memorial of the hurricane’s victims is to be seen in the neighboring photograph.

Another plaque says the Little Calumet River is designated as the African American Heritage Water Trail, but the only thing to see in the photograph to its left is a rusty bridge spanning the river.

One plaque says Chicago’s Finest Marina is the area’s oldest Black-owned marina, however the photo belonginging to this plaque only showcases an old white fence right next to a river.

At a cursory glance, nothing of importance is at these sites. Even at an in-depth look, there isn’t much. The only thing to denote that there’s anything historical about these locations — anything Black about these locations — are the plaques that rest nearby. But, without them, there is practically nothing.

Yet, at the very top of “Shore|Lines,” there is suddenly something: an explosion of life. Photographs showcase vignettes of life in Chicago, one of the historical destinations for Black people throughout the Great Migration. The photographs shown were not taken by Agu herself, but curated from the museum’s own collection to weave an intricate and diverse tapestry of the city through the lens of others. For the first time in the exhibition, the faces of Black people are actually seen, and Black life is actually shown. The final leg of “Shore|Lines” is a separation from the hazy showcases of Black history, and instead are firm assertions of Black history. The importance does not need to be spelled out; it is merely there by virtue of the photographs existing.

Be First to Comment