Waking up to a fresh cup of coffee before work used to be routine for Calumet Park resident Charlotte Pickens. That was before 5 p.m. on July 1, 2008, the day she walked out of her downtown office for the last time. Since her last day of work over two years ago, she has run out of unemployment benefits. She doesn’t qualify for other Illinois unemployment programs, but Pickens doesn’t want any more financial assistance; she wants a good paying job again.

Gov. Pat Quinn announced Tuesday that the two-month extension of the Put Illinois to Work program will keep close to 2 percent of the state’s unemployed in a job, but more than 670,000 Illinoisans like Pickens will have to wait for a program they qualify for.

Illinois is tied with Ohio as the state with the 10th highest unemployment rate — 10.1 percent. The federally funded Put Illinois to Work program helps the unemployed find jobs but requires applicants to meet certain criteria.

The Put Illinois to Work program pays the $10-an-hour salary only for low-income parents who are 18 to 21 and have a household income level less than 200 percent of the Federal Poverty Level ($2,428 a month for a family of two). Anyone who applies for the program must fulfill each of the those requirements in order to qualify. Since it began, the program has helped 26,000 people get jobs.

“Most of the people that I run into have been in the workforce for over 20 years or more,” said Pickens. “It sucks because there’s nothing out there.”

Roger Ehmen, the director of community re-entry services at the Westside Health Authority in Austin, said the program is designed to help legalized workers learn a skill set that will help them get in-demand jobs. Since 1990, the West Side social service organization has provided over 4,000 ex-offenders with job training and services to refine or learn skills. Even with the extension, the program isn’t helping many more people.

“Our program is very limited,” said Ehmen. “There are 21 slots for the whole year.”

Participants often get jobs at hotels, churches and insurance companies. This is not enough for people with work experience that have exhausted their unemployment aid, says Pickens, who used to be a supervisor for the Chicago Housing Authority.

“It’s good for that (18-21) age group, but they’re not the only ones who need work,” said Pickens.

Ehmen said there are no programs for middle-age adults with children over 17 who’ve been laid off. He suggested that these people try to find jobs the old-fashioned way, but Pickens said she’s tried everything. She’s frustrated that employers seem to want everything done online, and she says it’s impossible to reach anyone in a human resources department, even if you show up in person.

Jim Picchetti, jobs project organizer for the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless, said he wishes the program could be extended to as many people as possible because single people are struggling the most. He said with federal and state money and with contributions to these assistance programs from everyday people, it could work. The coalition said it’s pushing for exactly that: a federal job package that would include more people.

Elce Redmond, a community organizer for another West Side organization, the South Austin Coalition, said, “The state can only do so much . . . We really need a national job program that puts people back to work.”

To Ehmen, unemployment is a federal problem that requires federal money, especially since the state of Illinois is $13 billion in debt.

“The state is not a good source of money because they’re broke,” he said.

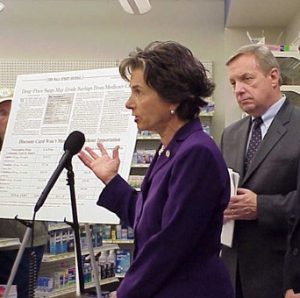

Democratic Sen. Richard Durbin introduced the U.S. Senate bill, S3816 – Creating American Jobs and Ending Offshoring Act, this week, and is facing off with Republican opposition. Still, Pichetti said, “There’s always more that can be done.”

Unless Congress decides to extend the program another year or adopt U.S. Senate Bill 3816, the Put Illinois to Work program extension will end Nov. 30.

Be First to Comment