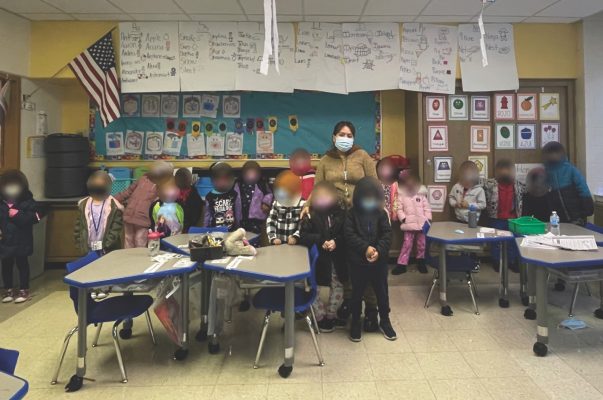

BEING A TEACHER IS one of the toughest jobs. Guadalupe Palacios, 26, is an elementary school teacher at Jefferson Elementary School in Berwyn, Ill. Palacios was born in the United States from Mexican parents and currently lives in Maywood, Ill. Although she struggled with identifying herself, she now proudly calls herself a Chicana, a blend of American and Mexicana.

Palacios has been trying to push the Spanish language into her elementary school. As a first-generation student, she managed to graduate from Dominican University. Her journey to figuring out everything on her own, from college applications to managing FAFSA was not easy, she said. At Jefferson, she wants to show her classroom the many cultures the world has to offer.

How would you define your race? Were you born in the United States?

I am first generation. I was born in the United States. I don’t feel I belong to either. I can’t say I’m fully Mexican, or I can’t say I’m fully American. I can definitely say I’m a mixture. I will always hold the question just because my dad would say, “you’re a Chicana” with my family. When I would go to school in Melrose Park, they were Italian, so I was never really classified as an American. Even at a school I felt like I was American, and then at home you’re not fully Mexican.

That’s how I always saw myself, like you’re in the middle. When growing up, what am I and what people say? “Oh, you’re Mexican American.” What does that mean? Really? I’m not fully Mexican, and for the outside world I am not a full American. So that is a very hard question to answer because I’m still wondering that myself. I guess I could say I’m Chicana, does that make sense? It’s different terms as [they are] used by everyone; I don’t know. So it’s a little hard. I think [that’s] something I have to figure out for myself now. I’m sure other first-generation folks [feel the same].

I have a couple of cousins who also felt that experience and I’m sure others in college as well. I went to Dominican [University] where I had a history class. I had a couple of students who felt, where are we in this balanced Mexican American? Where do we fall? That always depends, because there are some people who dominate more their Hispanic side versus their American side.

I do think where you live also affects that as well. I grew up in the suburbs. I feel I kind of leaning towards more on the American life, even with my youngest brother. He definitely dominates the more American side and my two other siblings dominate more the Hispanic side.

At home you’re being told something and then at school, a different thing. That makes you question, okay, what do I do? What do I identify with?

It’s a little tricky. It depends on the environment or the people. At school, teachers would be, “Oh, she’s Mexican,” but am I fully Mexican? No, no, I’m not. I can say my parents are Mexican because they came from Mexico; they were born in Mexico. But at school people would say, “She’s just Mexican.” I definitely think what people label you as also begins to affect you.

In my younger days in school there came a time where I didn’t want to be “Mexican.” I know my younger brother felt that too.

People don’t understand your culture. They just begin to do labels, like all Mexicans are always very drunk, and I didn’t want to be associated with that. I guess that’s why I also made myself—and I know there’s a word for it—blended in with the American culture. But now I feel like I’m more, “Oh, I’m more Hispanic.” I try to speak more Spanish.

I like to protect my Spanish because if not, in the future my kids would just be “fully Americans” and it makes it harder because like I said, I’m first-generation. I know my kids will be second, and in the school [where] I teach right now, my kids tell me, “I don’t like Spanish,” and I feel they are dominating that American side more. They just say, “I don’t know how to speak Spanish,” and I don’t like it. I have a blue card that means “English,” like English time, and they jump out of their seats, and I pull out the green card [Spanish] and they’re like, “Nooo.” I do things to help them identify themselves. It’s a little sad because that [Hispanic] culture is being left behind and it’s just becoming Americanized.

I agree that we have to keep that Spanish tongue going so it can continue to pass on. Now, what do you think of the term Latinx to identify people of Latin American or Spanish background?

I honestly didn’t hear that until later in college, maybe even in my junior year. I don’t have anything against it. I know there are some people who get upset [because] they want to be specifically identified as Puerto Rican or Mexican. I feel as Hispanic holders we are very protective of our country, and we don’t like being put as a whole. This might be an iffy subject but I know some Puerto Ricans don’t like being called Mexicans, but they don’t think it’s some offensive term for them. Or even vice versa. Some Mexicans don’t like being called that so I think the Latin theme it’s very interesting. I haven’t really gotten much into that topic. I guess I’m kind of closed minded on that. But I don’t think it’s anything bad. I don’t know. It’s kind of hard to understand the question.

“People don’t understand your culture. They just begin to do labels.“

Do you feel like Latinx is just an excuse to mush Hispanics cultures together, one word to combine all of them?

I think it’s a little biased, I guess. Especially in the Hispanic population. If they see someone that’s Chinese or Japanese, Filipino, they call them “chinito.” When they are not even Chinese! They’re Korean, from the Philippines, but I can see where people might be coming from, where we’re just being put into this whole bubble of just all the Hispanics. People not even get to know the culture itself.

Some people might feel like, “Oh, but we’re not all the same.” And that’s true, it even goes for Mexico. Not all parts of Mexico are the same. For example, Día de los Muertos is coming up. On my mom’s side they celebrate a little differently because my mom is from the capital versus how some people from Durango [state] celebrate. People feel really proud of the traditions and their customs and I don’t think it’s fair to be generalized. But we’ll just put them there like they’re all the same; all Puerto Ricans, all Mexicans. But there are different customs, different norms and cultures, different foods. For me personally, I don’t see anything wrong with [Latinx,] but I can understand where people are coming from.

You had mentioned that at some point, you didn’t want to be identified as Mexican. Has your experience as a Latinx person isolated you to the way you grew up, or have you been able to branch out culturally?

I think my elementary grade levels, and even some of my high school, I felt I wasn’t able to branch out with my culture. Maybe it was because of the environment. I grew up in the suburbs in an Italian area and I felt it was mostly Italian and Hispanics. It was half and half and some African Americans. And one or two Filipinos. I saw all of my teachers being white, except for my ESL teacher, and even though, she was from Spain. I don’t think I felt comfortable. We never really talked about the truth—except for African Americans and slavery. We never really learned where their traditions came from or their customs. Like in college, I loved learning about Ghana. I had to learn about a new continent and about their traditions. I did a whole PowerPoint and it was amazing. I didn’t know about their dances and stuff like that. [About my culture] it would have been nice to know [more] and if I would’ve seen that instead of the stereotypical tacos and Cinco de Mayo…

When they had Taco Tuesday in their lunch?

Yeah, and that’s all we had. I feel if I had seen more of my culture in my history class or even within their environment, if I just had seen more of Mexico and more of my traditions…

Would you say like Día de los Muertos? It’s a very colorful set up. Do you think if you had seen that in elementary school, you’d be, “Oh my god, that’s what my culture where I come from!” Would you have been more open to your culture?

I feel I would, especially because of my mom. She does her own ofrenda. But I feel I would have been able to relate to that as a student. Okay, I’m seeing that at school, and I’m seeing that at home. And the school didn’t have to put a big ofrenda. They could just talk about it for a day or two just to begin with. I do understand, as a teacher, the school wants a certain curriculum. But you’re also not embracing the culture of the students. So even if they had some kind of material I would embrace it and be like, “Oh yeah, I have that at home.” I’d want to share out and ask my mom more about it. If I don’t ask my mom, then that tradition goes away. If I don’t follow it for my kids, I definitely don’t think my grandkids are going to follow it because they’re not going to know what it is, if they don’t teach it in school and embrace that culture.

I think that where I grew up and the fact that I’ve always had white teachers, none of them ever spoke about a culture, other than tacos, rattles, and sombreros. I think about African Americans, I didn’t even really know about their customs and things of that nature until later. The stereotypes that the world has put on every race also made me feel kind of ashamed. Growing up they would always be like, “Mexicans are always drunk, Mexicans are racist, Mexicans are this and that.” I feel that seeing all those negative stereotypes is crazy. Even as a little kid, I was like, I don’t want to be associated with that. That also led me to my more American side.

I would have been able to branch out more if I saw more of my culture within the school, the classroom, more Hispanic teachers. Seeing more Black teachers as well. I would want to learn more about cultures and that’s where it began. We’re having these stereotypes, like, Mexicans are always being loud, they’re bad people, and we grow with that mentality. And then they’re just going to keep it going; it’s just never going to get fixed. So, some of us are like that. But it doesn’t mean that every Hispanic is.

How do you view Spanish as an attribute to your identity? How important is it to you?

I feel my Spanish is, on a scale of one to 10, a 10 or even more, I think being bilingual is an attribute. It’s something wonderful not even just for finding a job but also to keep embracing our culture. If we don’t protect our Spanish, then who is? Some teachers don’t care, even before then, when I was in school, it was always English. There were monolingual classes. It was English, English. In my district, there were no bilingual [classes] or if there was, it only was one class and it would always be full. I’m glad to see now that there are more dual classrooms. Now we can also embrace that Spanish and we can fully accept it.

“Growing up they would always be like, ‘Mexicans are always drunk, Mexicans are racist, Mexicans are this and that …’ I don’t want to be associated with that. That also led me to my more American side.”

Do you think you would be able to call yourself Mexican even if you didn’t speak Spanish?

Like one of my brothers, he doesn’t speak Spanish. He understands it but doesn’t speak it and sometimes we would joke and say, “Well, you’re not Mexican.” I know people would say, “Oh, how are you Mexican but don’t speak Spanish?” So I think it depends… for myself I would still identify myself as Mexican, because you could still celebrate the culture, embrace the traditions, customs, the holidays.

Would you say your culture is better than other cultures? Is it better than people who come from a different ethnicity?

I don’t think my culture specifically is better than anyone else’s. I do think we all have our own traditions, norms, customs. I respect everyone else’s even if it’s something weird. No, no, I don’t think it’s in any way my culture better than others or their culture is better than mine.

You mentioned all that you had an elementary school was Taco Tuesday and sombreros. Looking back at that, does that kind of bother you or in any way?

I feel in a way it does because it’s very seriously stereotypical. I never came home to my mom eating tacos. She wasn’t singing on the top of her lungs and having a pancho. It was just a normal day, that’s not even what we’re doing. But I definitely think those stereotypes affected me. Yes, we party; anyone does.

I work in the school and we feel, why can’t teachers think about what they teach and think about what is appropriate and what’s not? Dig deeper into what you’re going to teach and think about it because you as a teacher, you’re the leader, but you’re the one that’s enforcing all of this learning… Kindergarteners, first graders, second graders, they’re like sponges. They’re observing all of this and if every grade level is telling them every Mexican is a drunk, then don’t you think I may be one of those kids? It’s going to feel like, “Oh, I don’t want to be with that.” I know I was thinking that [in school]. I wanted to be normal. I don’t want to be known as the one that always got drunk or a woman always getting arrested because we’re illegal. Just on sight, boom they’re illegal. There was never a time where I wouldn’t hear these two words combined in elementary, Mexican and illegal. Always came together. That really bothers me. I’ve been there before.

In college I wrote about the negative stereotypes and the impact that had on them and yeah, it was always Mexicans, illegal, illegal, Mexicans, Mexicans, aliens, aliens. Always. All the time. In the education system we need to better the way we implement those people’s beliefs and everything into every child, and not just our Hispanic cultures, but also other cultures. Like I said, “Oh Korea, same thing like China, same thing as [The] Philippines.” It’s just a bundle. It doesn’t matter. It’s all the same. They’re all Chinese people. These are all Mexicans, and Mexicans are all drunks. And the Asians and all of them are super smart. And I don’t think that should ever be the case because then kids aren’t going to want to embrace their culture.

I think that’s where it starts with how others are implementing it. How we’re being defined because it’s also at home [where] they’re telling you’re not Mexican. Not fully Mexican; you’re Chicano. It’s true. But if you’re telling me that I’m not Mexican, that made me think, “Okay, I’m not Mexican.” I’m not going to want to embrace that part of me.

I think it’s also teaching little kids, maybe you didn’t learn English first, but we’re going to learn Spanish together and that’s what I tell my kids too. Because a lot of them don’t want to speak Spanish. They say, no, no, I just like English. But I know they know some words. When they see everyone else speaking English, they say, “Why can’t we speak English too?” So it’s very hard.

Be First to Comment