At the age of 19, no one expects to start a major magazine that has a lasting historical impact. Imagine 19-year-old video editor Dan Sinker’s surprise when he did just that. 30 years later, Punk Planet has gone down in history as one of the most popular independent music magazines, with all 80 issues preserved for generations to find on the Internet Archive (at least until it was recently hacked and taken down). It’s back now, but absence only makes the heart grow fonder, so let’s reflect back.

Sinker sets the scene. It’s ‘93. Nirvana’s “Nevermind” came out two years ago, rocketing a small indie band from Aberdeen, Washington to national stardom. Record companies’ sights — and paychecks — became squarely focused on signing any half-decent rock bands playing in local clubs who could possibly be the next Nirvana. Needless to say, it is a fruitful couple of years for punk music, and anything adjacent. A steady cash flow into the scene nurtures youngling bands and DIY projects into a healthy, thriving community.

The World Wide Web was also publicized this year, but before that there was something else — America Online, which Sinker used to talk about his favorite subculture with other apostles online. The latest thing making ripples on the message board was the editorial policy of America’s only popular punk magazine, Maximum Rocknroll. If you were anybody who was doing anything — be it in a band or running a DIY label — you were trying to get published in Maximum Rocknroll, because that was the only way to be seen on a national scale. (And to be seen as the next Nirvana.) Maximum was overwhelmed by the amount of records coming in for review, so they instituted a policy: only “punk” albums would be publicized.

“It’s a very, very, very poorly articulated policy, because everyone submitting those records thought they were submitting punk records, or most people did,” Sinker comments. “What it really was was a very regressive ‘We’re going to define this by a sound that was redundant.’”

Sinker made a post on the message board: “Well, why couldn’t we start a magazine of our own?”

Then he got locked out of his apartment for the weekend.

He came back two days later, cut off from his computer, only to find an entire group of people volunteering to help. So Punk Planet was born.

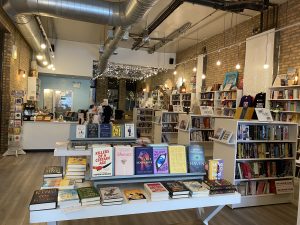

It was unique in the fact that, while it was based out of Chicago on the reliance of Sinker, they had contributors from across the nation. “We were a virtual newsroom, which didn’t exist, it was all email or literally mailing discs to each other,” says Sinker.

The first edition was put out two months later with reviews and interviews from across America, mostly by beginner writers emailing in their articles from Washington, Pennsylvania, California and of course, Chicago.

Sinker became lead editor of the voice of a subculture in less than a year. Within five years, the team moved into a small office and it became his full-time project. Issues famously ran in the hundreds of pages with their in-depth interviews — and their endless record reviews, as they tried to make note of every one sent into the office.

Sinker never expected to be a journalist, but in a sense he always expected to be an editor. He graduated from college in 1996 as a tape video editor. The summer after he graduated, all the tape editors at his school were replaced with Macs. Although his medium was lost, his editing skills weren’t.

“Storytelling is medium-agnostic, right? And then editing is medium-agnostic. I realized that editing tape and editing words was the same thing, it just was different in terms of how you used your hands,” Sinker says. “Ultimately you’re using it in the same way, which is to tell a better story.”

Be First to Comment