Making a video game is a lot like playing one. There are rules to follow, screw-ups to make, objectives to meet, and in order to finish these objectives, communication is necessary. That last part was especially true for five college students, who lived in two cities yet enrolled in the same game design course. They were tasked, despite their long distance relationships and creative differences, to make their video game PsychoSurgeon in less than three months.

Press Start

For nearly ten years, computer science associate professor Jason Leigh has taught the computer science course, “Video Game Design and Development” at the University of Illinois at Chicago. What is notable about the class is that it is not only interdisciplinary, but it is also taught in conjunction with another classroom at Louisiana State University.

Leigh started UIC’s video game design class in 2003. “When I received tenure as a professor and was asked to take over a multimedia class, I decided it would be fun to convert it to a game class,” said Leigh in an email. After giving a lecture at LSU in 2007, Leigh was approached by Ed Seidel, who was founding director of LSU’s Center for Computation and Technology. Aware of Leigh’s class, Seidel asked him if he could teach it remotely from Chicago, as LSU was in the process of making their own multimedia curriculum. “Everything was easier than we expected because we were both on similar class schedules and time zones,” said Leigh. Around the same time, Robert Kooima – the current LSU half of the Leigh’s class – was still a student at UIC, finishing his postgraduate academics. After graduating, he moved to LSU to become a postdoctoral scholar, but then became a full-time faculty member and eventually Leigh’s teaching partner.

On the course’s webpage, there is a list of topics that indicates what students will learn, things like “taxonomy of video games,” “software architecture for video games,” “game AI (artificial intelligence),” and so on. But the biggest challenge is learning to work with others, especially those who live in another city. “The biggest challenge [for the class],” said Leigh, “is team coordination.” During a semester, students from the two schools form a team – a “mini game company,” as they call it. For less than three months, each team has to make a game based on a theme the professors choose. The theme for the semester of spring 2012: low-budget movie tie-ins. “When we first started to do this about five years ago, we were concerned that students may not have the video conferencing gear to communicate,” Leigh continued. To counter this difficulty, Polycom units – videoconferencing systems that looks like horizontally-flattened tripods – were installed in the classroom. It got easier when Skype became more popular, though there was still a caveat. “It’s difficult for students to organize themselves remotely,” said Kooima, who categorized this as an “us vs. them mentality.”

Co-op Mode

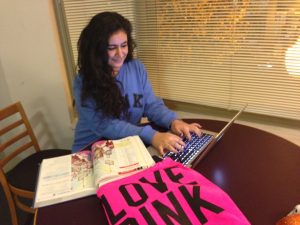

Tiger Fighting Dragons Games (the name comes from the two schools’ mascots: UIC’s dragon and LSU’s tiger) consists of five students: Laura Bronkhorst, Christian Dell, Alex Reeser, Ian Spaulding, and Meriya Thomas. Three are from UIC – Bronkhorst, Spaulding, and Thomas – and two from LSU. Four are computer science students, while the fifth – Bronkhorst – is a biomedical visualization graduate student and the team’s artist. Team members corresponding remotely with each other was an expected challenge. Given the abundance of free internet resources, they had well-thought ideas on how to communicate with each other. “We did Google Hangouts [Google’s video chatting service] when we needed big discussions, but that didn’t always work well because people would be in random places,” said Alex Reeser, the team lead from LSU. When it came to using texting services, things went smoother, but still awkward. “Sometimes we wrote whole essays back and forth about design decisions,” he added. Bronkhorst elaborated on the team’s less-than-positive communication issues, echoing the “us vs. them mentality” caveat that Kooima mentioned. “It felt like the three of us at UIC were always on the same page, and the two LSU guys were [likewise], but occasionally the five of us were just not [in agreement],” said Bronkhorst. She added that it was the lack of face-to-face conversations, especially through video chatting, that exacerbated the team’s issues. Dell, the other programmer from LSU, conceded that having students correspond with each other remotely was beneficial to let everyone experience it at some point. “In the real world, you won’t always be working with people at the next desk over,” said Dell.

Birth of a Game

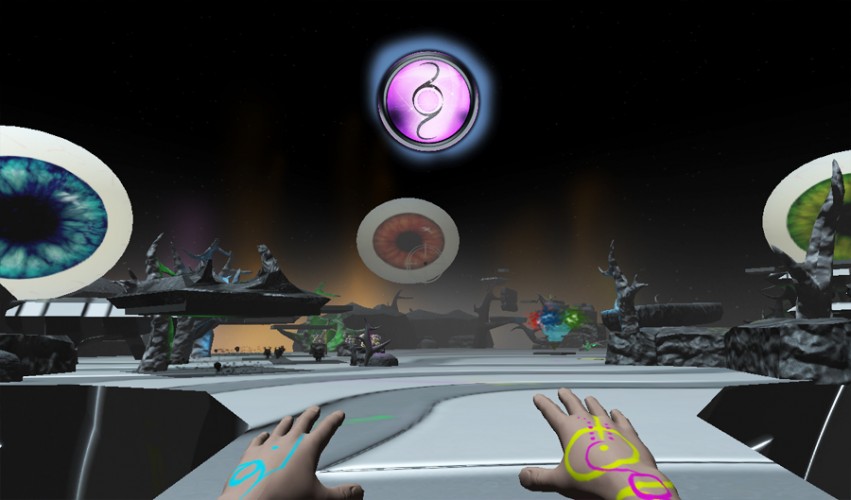

PsychoSurgeon, the team’s project, is a puzzle-action game viewed from a first-person perspective. In it, a player navigates around a space-like, psychedelic environment, fighting shadowy creatures, avoiding traps, and manipulating objects with powers they gain as they move further. There is no tutorial, but floating phrases and statements appear when a player approaches specific parts of a level. Coming up with PsychoSurgeon, let alone a game concept, was no easy task. Each member had his or her own idea of what each wanted to make, like an action game in space, a space racing game, or a psychedelic adventure game. “We initially went with [a space racer idea] because we thought it would be relatively simple,” said Reeser. Leigh and Kooima told them that executing this would be complicated, but gave positive responses to their other ideas. The problem was that they had trouble picking only one idea and satisfying everyone by using every idea each member had. Even though the instructors responded positively, Reeser and Dell lament that the time they spent coming up with concepts would have been better used as time spent making the game. Ultimately, they took elements of each member’s contributions and combined them into one game, which ended up being PsychoSurgeon.

The communication issues were not only related to the long distance, but also to interdisciplinary studies. “For most students in the class, they have never worked with students outside of their discipline,” said Leigh. The split between computer science and non-CS majors is half and half, but there are cases when the split is lopsided and those on either side will have to go out of their comfort zone, like programmers doing art or vice versa. But the point of having interdisciplinary studies as an element of the class is so that students learn to “bridge cultures,” as Leigh put it. That was difficult for Bronkhorst, who said that conveying visual ideas to programmers was difficult, partly because of her limited understanding of what they were doing, programming-wise. Visual ideas she came up with would be too difficult to program; concepts they presented her would be too arduous to animate and model. It did not help that there were arguments over having one’s own idea stay in PsychoSurgeon. “It’s tough, because anything you create becomes personal, so I understand why they wanted to keep things they created,” said Bronkhorst. Coming from an art background, she said she is used to getting feedback on her work, which she supposed is not what programmers are used to. Despite this, the other members had positive things to say about her work. “She really owned making the game look how it is,” said Reeser, who also said that she was quick to learn how the game editor works.

Attract Mode

At the end of the semester, teams showcase their games not only to the class, but industry professionals as well. As stereotypically broke college students, Reeser and Dell could not travel to UIC to be with their team. Reeser admittedly thought that their presentation was uneven, since some members were better at demoing the game than talking about it and vice versa. “It was initially intense, but as I explained more…I grew more confident, because I knew the ins and outs of the project,” said Reeser. Luckily, playing the game was more important than talking about it. Despite bugs and criticism – no video game has ever existed without either – the crowd enjoyed PsychoSurgeon. “We got the ‘wows’ and the ‘oohs’ that we wanted to hear, when we wanted to hear them,” said Bronkhorst. Getting positive response – especially for a game made in three months – would have been enough for anyone. However, PsychoSurgeon ended up winning “Best Graphics” and “Best Gameplay” in the class.

Those in the team who graduated went on to become employed. Meanwhile, Reeser spent time fixing, tweaking, and adding whatever was needed in the game; a few weeks ago, he submitted PsychoSurgeon to the Independent Games Festival as a student entry. There is no doubt that the positive reinforcement gave the team confidence in their work and their skills.

“While I always had that dream, this class – and the support of Jason Leigh – served to assure me that I actually should pursue a career in gaming,” said Bronkhorst, who, after the class, finished research for her master’s degree. “Two years ago – even a year ago, really – I would have never guessed that I’d be doing any work in games.”

(Image/Video credits: Tiger Fighting Dragons, UIC)

Be First to Comment