Chicago’s monthly Police Board meetings are intended in part as a forum for citizens to air complaints about Chicago police officers before the appointed Civilian Review Board that reviews disciplinary actions meted out by the Independent Police Review Authority. Citizens are allowed to speak for two minutes, but attendance is usually low and the meetings typically last less than a half hour.

A meeting last September was even shorter than most, with a total running time of about six minutes. Only two citizens spoke. The first was Robert More, who lugged his laptop up to the microphone and rambled about perceived inconsistencies in the department until Board President Demetrius Carney cut him off.

Next up was Larry Marshall.

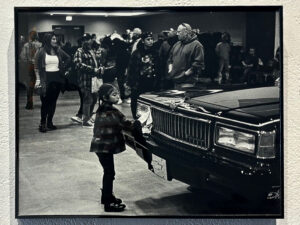

Marshall has attended most of the Chicago Police Board meetings for years, seeking justice for the alleged assault of his granddaughter by Chicago police officers in 2003. In this meeting he spoke only briefly – a contrast to his typical long speeches. Marshall blamed his brevity on a “bad mood,” influenced largely by his growing feeling that the police department will never deliver what he considers justice in the case.

Marshall is in his 60s and stands almost 6 feet tall. Long gray dreadlocks give him the appearance of an urban sage.

On this day, Marshall was missing his usual wingman, George Willard Smith. Smith, like Marshall, is one of the few people who attend almost every meeting. The two met at a police board meeting years ago and have been allies ever since. Smith often yells out of turn at the meetings, once proclaiming, “Why don’t the police turn in the bad cops, and then lead by example!” These outbursts got him temporarily barred from the meetings by Carney.

Marshall will never forget April 3, 2003, when, he said, three plainclothes police officers in an unmarked car chased down and attacked his 11-year-old granddaughter, Timia Williams, in her neighborhood around Central Park and Ohio streets. According to Marshall, they handcuffed her and punched her, resulting in bruises on her skull. The incident landed her in the emergency room.

According to Marshall, the police were holding a drug dealer in the car when they ran after Timia.

“I suppose they made him point out someone,” he said. “Then they grabbed her.”

Timia was on her way to a local store at around 3 p.m. when the car cut her off, Marshall said. One of the officers rolled down the window and called her over to the car. Timia, not knowing who they were, started to run. The three cops leaped out of the car and chased her, Marshall said. When they caught her, they slammed her on the pavement, and handcuffed her, he said.

Spokespeople for the police department and the Chicago Police Board promised to respond to multiple requests for comment and FOIAs regarding the incident, but never followed up with the requests.

“By that time, the whole community saw it, and they came and got my oldest daughter,” Marshall said. “She went down there and demanded they release her. They tried to say she had drugs, but she didn’t have no drugs. They released her and didn’t identify themselves to no one. Luckily, someone in the community got the license plate number. When I came home and saw my granddaughter like that, that was real upsetting. ”

Marshall filed a lawsuit the next day. The case went to trial, but the outcome left much to be desired, he said. Marshall said Timia’s mother received a small settlement from the department. And Marshall himself, who had been raising Timia since she was six months old, got nothing.

“I wasn’t looking for money anyway,” Marshall said. “I was looking for some kind of justice. We have a long way to go.”

Six months after the case went to trial, the Chicago Police Department issued a 15-day suspension to the three officers. They appealed, and served only a three-day suspension, according to Marshall. In response to Marshall’s complaint, the officers said that Timia appeared to be 16 years old, Marshall said.

“What has that got to do with it?” he said. “I don’t care if she looked like 100. That’s no excuse for them to attack her.”

Despite the lack of response, Marshall hasn’t given up the fight to get the officers who allegedly assaulted his granddaughter off the streets. He says he wants to see the officers “suspended forever.”

“I wasn’t concerned about them being incarcerated; I really just wanted all three of them suspended,” he said. “So at least we could be able to walk down the streets without being attacked.”

Statistics bear out Marshall’s complaints about the police board. The board’s main purpose is to review the disciplinary measures meted out by the Independent Police Review Authority, and decide whether to uphold, negate or alter disciplinary actions.

But critics say the board is biased in favor of officers. The board has a history of reducing and overturning suspensions, as documented by The Chicago Justice Project’s 10-year analysis of board rulings. The review, carried out by Justice Project founder Tracy Siska, showed that from 1998-2000, the board voted to refuse the discharge of nine police officers who were found guilty of charges of violent and criminal behavior. In 63 percent of the cases where the police superintendent recommended firing an officer, the board overruled him and the officers kept their jobs.

Kaaren Fehnsenfeld, a clerk at Olivia’s Market, frequently attends board meetings. She described watching as one woman with a complaint against officers was essentially ignored by the board.

“It was crazy because as each person stood to make their case in front of the board, they seemed absolutely bored,” she said. “It was a pretty disheartening look at our democracy.”

The same year Marshall’s daughter was allegedly attacked, the department published a “Status Report of Investigations of Allegations of Unreasonable Force” from January 2003 to December 2003. It found that of 1,150 unreasonable force complaints filed, only 80 resulted in disciplinary action.

Hence it’s perhaps not surprising Chicagoans are cynical about police accountability.

“Police abuse will continue without vigilant citizens to take on the police misconduct,” said Larry Mitchell, a sales representative at Quality Tools and Abrasives and resident of Elgin.

“I do feel that the police promote a culture within its ranks that they are above the law,” said Tak-Seng Lo Dro, a Buddhist clinical psychology doctoral student in Naperville. “I see this in a lot of little ways, running red lights, making illegal turns when they are just driving around, and pulling people over simply because they reacted negatively to them while in traffic.”

Marshall wants to appeal to the new mayor, upon election, to put an end to board meetings since he believes they are a waste of time.

“I don’t know a person they’ve helped in years,” he said. “The board really ain’t no good. It’s a waste of our tax money.”

Michael Ranieri of the Moyer Foundation feels that Mayor Richard Daley should have responded to Marshall’s complaint. “Daley was completely wrong on this issue, it was like he was rubbing his position in the faces of everyone under the law in the city.”

Marshall said he’s not sure how much longer he will keep going to meetings. He might hang in for another 10 years, but he’s doubtful anything will change.

“They don’t want the truth,” said Marshall, “Nobody wants the truth. I just don’t understand it.”

Be First to Comment