With the end of the Iraq war and the whining down of the war in Afghanistan, veterans returning home will be faced

with a long road of difficulties.

Veterans have proved themselves in a world where stress, danger and life-and-death decisions were routine. They will now have a harder time back home navigating a calmer but uncertain terrain — the job market.

Matthew Saldana, who served one tour in Iraq and a second in Afghanistan, hasn’t worked full time in 18 months. He’s scoured “‘help wanted” listings, taken college courses and earned an emergency medical technician certificate. But he finds himself pigeonholed.

“What do you come out with having been an artillery man or in the infantry?” he said. “The best job you can get is security. That’s not what I want to do for the rest of my life.”

His dream is to become a Chicago firefighter — he’s been on a waiting list five years. He’s survived mostly by working security– he’s a fill-in sub at one company and also earns a modest on-call fee as a firefighter-EMT in a southern suburb.

“I’m barely pulling through,” he said. “I’m drowning. I need to find something fast.”

One organization in the U.S. that helps veterans find and stay in stable jobs is Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America.

“We’ve had to be entrepreneurial and innovative and think on the fly and manage people and logistics … we know that we have the skills,” says Matthew Colvin, who advises companies on hiring veterans. “But it’s hard to convey our worth a lot of times because we know it in military terms, not in civilian terms.”

Veterans in Chicago had been given another opportunity Memorial Day weekend when Mayor Rahm Emanuel launched a “Returning Veterans Initiative” to help find jobs, drive down unemployment rates that now triple the national average and smooth their transition to civilian life.

“It is essential that, as a city, we are prepared to welcome these men and women back and are prepared to help them find employment, resources and other assistance as they integrate back into civilian life,” the mayor said in a press release.

For some veterans who have returned home, battling the frustration and dissatisfaction of the two wars’ outcome and repercussions had settled in.

“Sometimes we hide the fact that we’re veterans,” adds Colvin, an Air Force vet of two tours in Afghanistan. “I don’t think that’s the way it should be. … We’ve got more life experience than the kid coming out of college or even the guy who’s maybe equally qualified on paper.”

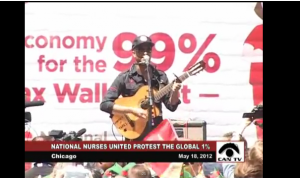

During the NATO Summit held in Chicago, Sunday, May 20, dozens of anti-war veterans tossed their medals onto a street near where the summit was held calling them “representations of hate,” “lies” and “cheap tokens.”

Sgt. Jacob George, who served three tours in Afghanistan, said before throwing his medal, “I do not feel like the intentions of the overall mission matched my intention just as an individual, and most of the people who served as well. So, I’m will to give this back and even though it is a very emotional thing for me.”

Other veterans were not so stricken by the symbolic gesture they were doing by throwing away their metals. One veteran felt a “weight lifted” once he threw his.

Ash Wilson, a veteran who served in Iraq in 2002 and 2003 said, “What I saw there crushed me. I don’t want to suffer through this again and I don’t want our children to suffer through this again. So, I’m giving these back,” and with that Wilson through back his medals.

The protesters cheered the post 9/11-era veterans on, clapping and yelling, “give them back!”

“I choose human life over war,” Jerry Bordeleau shouted through a microphone, before tossing the medals onto the street.

More than 1.6 million troops are back from the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Emanuel’s “Returning Veterans Initiative” is aimed at tackling the hardship of finding employment for many of those returning. Although this helps those in Chicago, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce has established the Hiring Our Heroes program, sponsoring about 150 job fairs around the nation, working closely with about two dozen major employers, as well as thousands of smaller companies.

Their goal is to hire a half million veterans and military spouses by the end of 2014. Several companies have already committed to adding more than 10,000.

With organizations and initiatives being established to help veterans, more and more are looking and applying for jobs with optimism that eventually they will receive employment.

However, like many other vets, Saldana misses the Army’s anchors: a sense of camaraderie and its steady income.

“Here you’ve got to worry about how you’re going to find money to eat and how you’re going to pay the bills if nowhere will hire,” he said.

Be First to Comment