“When I die, bury me—in my beloved Ukraine,” wrote the Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko in 1845. Although the days of freedom from Russia had yet to come, the writer from the village of Morintsy was already addressing the importance of a united country.

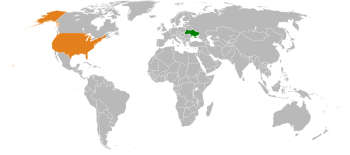

The path toward unification started in 1994 with the Budapest Memorandum. The fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 opened the path to a deal between the United States, the United Kingdom, Russia and Ukraine. The newborn country gave up its nuclear arsenal in exchange for preserving its independence.[pullquote] Hear the Ukrainian language. [/pullquote]

The agreement was meant to keep world peace, but the recent invasion of Crimea ordered by Russia President Vladimir Putin broke the region’s fragile stability and its tie with Kiev. the capitol of Ukraine.

“We are worried about Ukraine remaining a free, democratic nation,” said Pavlo Bandrivsky.

He is the second vice president of the Ukrainian Congress Committee of America Illinois branch (UCCA) was born in 1949 in the United States, but his heart is in Ukraine.

The hearts of Marta Farion, Motria Melnik and Esfir Barabanova also lie in the eastern European country.

New and old generations, all feel a strong tie with their homeland. They might have been born in Chicago –like Melnik- or in Italy –like Farion-, but they still speak Ukrainian. They might have escaped from discrimination –Barabanova’s family was Jewish- but they all consider Kiev their capital.

Despite the different background and life experiences, all three of the Chicago immigrants share the same desire: to see the West take action against Putin’s illegal military invasion.

The international community has responded with economic sanctions. The United States has frozen the assets and imposed a traveling ban on Kremlin’s collaborators, while the European Union’s list also included military commanders.

Sanctions might not be enough to stop Vladimir Putin, said Bandrivsky. Chicago attorney Julian Kulas agrees.

By the time the Budapest Memorandum was signed in the mid-90s, Kulas had long since left the country. The 79-year-old attorney and U.S. Army veteran moved to Chicago in 1950.

Kulas spent only eight years in Ukraine, although his roots are in the Western Ukraine community of Jaroslaw.

His father Anton was a cabinet maker, and the Germans forced the family to Oberstenfeld, Kreis Ludwigsburg (Germany) to work. Anton Kulas worked in the Wertz & Fisher Moebel Fabrik furniture shop, while his son Julian went to school and learned English.

Germany let the Kulas family immigrant to the United States a few years after World War II ended.

Kulas moved with his parents and his three siblings to Savannah, Georgia. They were welcomed by the locals who were both friendly and intrigued by people who spoke a different language.

A year later, his parents decided to move to Chicago to join the Ukrainian community, which –according to the 2000 census- amounts to 46,000 residents.

Kulas has been back to Ukraine through his work as a colonel in the U.S. Army Reserve, but he never thought about moving back to his homeland.

“I consider myself as an American with Ukrainian elements,” he said. “I feel an obligation towards the United States because people helped us.”

Both Farion and Kulas consider themselves American, and they both believe in the defense of human rights and freedom.

“Our world is interconnected, our economy and our politics depend on each other. No one can be isolated in this world,” Farion said.

Farion is the president of the Kyiv Mohyla Foundation of America, which is based in Chicago. She was born in the Vatican City, where her parents escaped after World War II, and she grew up in Buenos Aires. When she was 15, her family moved to Chicago.

Farion became a citizen of the United States when she was 18, so she feels more American than Ukrainian.

She remembers entire families in the Ukraine being sent to Siberia to forced labor camps, while others were uprooted from their homes after World War II. Both calamities afflicted Farion’s family.

The Ukrainian community of Chicago has been protesting in recent weeks outside Ukraine’s Consulate –at 10 East Huron St.– through candle light silent parades and through vigils to honor the hundreds people killed by snipers in February.

Neither Farion nor Kulas know what will happen, but Bandrivsky is sure that “it only works if the United States and the European Union are united.”

It is national interest of the United States government to help Ukrainians, Kulas said.

“Russia has enslaved Ukraine for centuries, and its population doesn’t want to be enslaved anymore,” Kulas said.

And Russian President Vladimir Putin doesn’t seem willing to give up on his dream of re-building the Russian Empire.

Kulas maintains that the March 16 referendum that overwhelming supported annexing the Ukraine to Russia was a public relations event.

During that vote, 97 percent of the Crimean population voted to secede from Ukraine, but the international observers suspect electoral fraud. The plebiscite’s results gave rise to suspicions in the Chicago Ukrainian community, too.

Both Farion and Bandrivsky defined the ballot a farce, and they worry it will legitimate further Russian invasions.

As a retired commander of the U.S. Army Kulas went back to Europe during the Cold War, witnessing the dictatorial reality of the Soviet Union.

Farion, Kulas, Bandrivsky and Barabanova all say they about Ukraine’s future.

“I want to cry. I feel sorry because Kiev is my city,” said Barabanova said.

Be First to Comment