A recent New York Times investigation across all 50 states revealed that policies surrounding groundwater usage were outdated and lacked uniformity, raising the risk of inaccurate conservation of the vital resource. Illinois in particular has faced problems with improper regulation last year.

A 2022 investigation published by Grist revealed that Joliet, one of the largest cities in the state, and its neighbor Will County, will no longer have access to clean water within the next decade with its current process of relying on their sandstone aquifer. Aquifers are bodies of porous rock that filter water naturally and produce clean groundwater. For the last century these counties have mined theirs to near depletion, leaving behind water too salty for consumption. This has resulted in plans to tap into Lake Michigan, like Chicago already does.

Robert Hirschfeld, the senior water policy specialist for Prairie Rivers Network , a clean water environmental agency organization, said that at the state level, Illinois relies on outdated common law.

“It’s the law of reasonable use. So you can withdraw and use groundwater so long as you’re not reasonably harming someone else who is above that groundwater,” he said. Aquifers can span acres, meaning that they aren’t really anyone’s. “That’s the thing with water: it’s an aquifer, it’s under a lot of people’s land. So it’s really a shared public resource, but private interests don’t want the government telling them what they can or can’t do.”

As far as more recent law, Hirschfeld said there hasn’t been much improvement.

“In 2010 it became mandatory, you had to report if you were pumping out 100,000 gallons a day. But there’s no teeth in the law. Right? There’s no penalty. And so very few people report that,” he said.

That is not to say that there have been no movements towards water conservation in Illinois, it just occurs more commonly at the municipal level rather than the state level, and varies greatly due to a lack of guidance.

Hirschfeld doesn’t think the state has the full suite of information or enough plans to adequately protect its water supplies into the future. “I actually think we want to be here in perpetuity, right? As humans occupying this land. So we have to plan for forever,” he said. “We just launched a new campaign called Clean Water Forever. Because we really need to be thinking about it in terms of forever, whether it’s quality or quantity. There are things that we could do to protect our water resources, but I don’t think we’ve done what’s necessary.”

There are four pillars to the CWF campaign: quantity of groundwater, quality of that water, access to it and equitable, accessible entry points for all consumers. In the short term, the campaign hopes to organize communities, raise awareness about pollution of surface waters and urge them to demand a future with clean water. The end goal is to propose laws and policies that will accomplish the goal of making sure that everyone has access to clean, affordable water.

Unlike at the state level, many municipalities in Illinois at the village level have realized the importance of groundwater and have created more strict monitoring systems.

Janet Angoletti served as executive director of Barrington Area Council of Governments for 20 years, before retiring while still maintaining a contract to continue her administrative services on several of the groundwater programs she started. Unlike many other counties, Barrington had a plan. The Comprehensive Land Use Plan was set in place for water conservation before Angoletti even took office two decades ago. “That’s a little bit unusual in the planning field. Usually there are city plans, municipal plans and county plans as well. But a regional plan was unusual at the time that was developed, and that was back in the early 1970’s,” she said.

The plan had several ecological studies behind it, all done in the late 1960’s and ‘70s. Angoletti said there were two major tenants to their plan in the ‘70s. “One is managing development to fit the needs of the area [and] the desires of the area,” she said. “The second is to protect natural resources or to build only the development that the natural resources of the area could support.”

There was mention of groundwater in this plan, but at this time it had been studied very little.

“When I started in 2000 as director at BACOG I looked through the plan. I read it. I looked for things that I thought were important, and that’s what stood out to me. Here’s a resource that everyone in the area, whether you’re a business or a resident or passing through, everyone uses groundwater as the water source,” she said.

One of the first things Angoletti did as director was create a committee to address the issue. They asked for volunteers to join the committee, one of them being hydrogeologist Dr. Kurt Thompson. They went through around 110,000 well logs and within the first three years created a three-dimensional model of the shallow aquifer system in their study area. In a partnership with the United States Geological Survey, BACOG converted some wells into monitoring stations that constantly monitor groundwater levels. BACOG partnered with other municipalities in order to complete their plan, but many other municipalities simply can not afford to replicate BACOG’s plan.

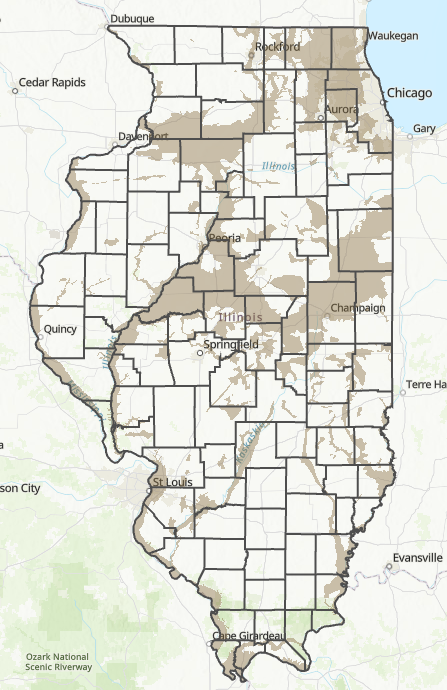

In order to truly understand how groundwater moves, you need to map a large area, sometimes larger than the municipality itself. Many turn to the Illinois State’s Geological and Water Surveys to understand how groundwater moves. Illinois’ water survey is one of the best in the country and provides detailed information.

Lisa Woolford, director of green initiatives and business development for ILM Environments, a public and government service dedicated to the conservation of local land and water in the Chicagoland area, said that one issue plaguing aquifers — in addition to overuse — is development. Woolfard said development of cities can mean more entities pulling upon the aquifer but it can also mean, “impacting recharge areas where rain can make its way down to fill the aquifers back up again,” she said. Recharge areas are areas where aquifers collect the most of their groundwater. Without them, aquifers become less productive.

“If you’re gonna go and build a Walmart in that area, you’ve taken away that groundwater recharge site. It’s going to affect the residents of seven to eight municipalities. So BACOG will work to defend that groundwater recharge area to make sure that we’re not doing damage to the aquifer system,” she said.

Woolford said that she is starting to see other municipalities shift away from such a reliance on groundwater. “That’s where municipalities like Elgin now tap into the Fox River for their drinking water. Lake Zurich now pipelines to Lake Michigan for their water.”

Woolford, Agnoletti and Hirschfeld all invite those interested in ground water conservation to reach out to their local municipalities and ask what they do to protect the invaluable resource. In addition, each one of their organizations have published information on their respective websites on how to help preserve natural groundwater.

“These programs are useful for people and knowledge is power,” Agnoletti said. “If you don’t know what’s going on, then you don’t know anything. You don’t have the power to control it, change it, improve it.”

Resources to Get Involved

BACOG Water Resources Model – understanding the creation of the Aquifer Model

BACOG Water Level Monitoring Program With Updated Information

Be First to Comment