Oak Park resident Chris Olson wants to be able to choose between two candidates this election, but for all practical purposes, his state senator has already been decided.

Olson is among many Illinois voters who have less to worry about when they go to the polls on Nov. 6 because their state senator, Democrat Don Harmon, currently in his third four-year term, is running uncontested.

“To have one person running seems kind of silly,” Olson said. “You’re supposed to have a choice. When you only have one person running, it negates that whole process.”

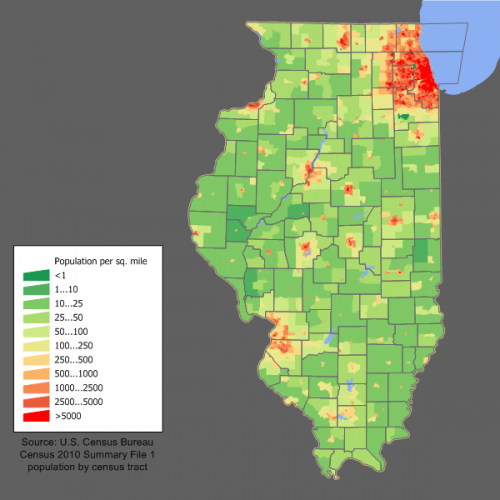

Harmon, who represents the 39th District, is not the only senator with no opposition. Fifty-one percent of the state’s 59 senators are guaranteed to win their election this year, and 31 percent of those senators are located in Chicago.

These numbers do not come as a shock to Dave Morrison, deputy director for the Illinois Campaign for Political Reform. “It is fairly common for legislative races to be uncontested,” Morrison said.

The main reason for uncontested political races is redistricting. The legislative map is redrawn every 10 years after the U.S. census to minimize competition, said Kent Redfield, professor emeritus of political science for the University of Illinois at Springfield.

The map can be drawn to favor one party over the other because it tries to deal with changing political demographics of the state, Morrison said.

“A big part of why [politicians] are uncontested is because there is no viable way for another party to get votes in that district,” Morrison said. “It would be a waste of time and money.”

Harmon, appointed president pro tempore by Senate President John Cullerton in 2011, is on the Illinois Senate Redistricting Committee. Harmon said he believes uncontested races still reflect a democratic process.

Democracy demands that an incumbent is accountable to the voters, be it in a primary or general election, said Harmon.

“The true contest [for me] happened in the primary election.”

“It has been a few years; I’m not sure where to find him,” said Harmon, of the March 20 primary.

Morrison, however, is not so sure this process is democratic.

“On the one hand, if no one runs, then voters have no choice. That’s not a feature of the system as much as it is of candidates deciding not to make the effort,” Morrison said. “[The word] elect comes from the Latin root meaning to ‘choose,’ and if there’s only one candidate, then voters aren’t choosing so much as ratifying.”

Although running unopposed, Harmon said he still campaigns by attending community events and mailing campaign literature.

“Running unopposed is easier, but you don’t want the election to slip past without connecting with voters,” Harmon said.

Harmon said he believes campaigning is important because he has some new constituents due to redistricting and wants to build relationships with them.

“I’ve had to say goodbye to some old communities, which is bittersweet,” he said.

Since his first race in 2002, Harmon has run with and without opposition. He said he campaigns the same way each time, but with less worry when unopposed.

“There are only two ways to run for election,” he said, “Unopposed or scared.”

Harmon may have less to worry about, but residents like Olson do not think uncontested races represent the electoral process.

“There’s no way for one side to have a voice,” Olson said.

Pam Myerson, a long-time Oak Park resident and lawyer, does not think a Republican opponent would have a chance in such a Democratic area.

“To some extent, I think this speaks to the fact that people are satisfied with the work that’s been done,” she said.

Be First to Comment