Editor’s note: This is Part Two in a three-part series on led poisoning in Chicago. Read Part One and Part Three. Also, see the results for playgounds tested for lead.

Story By Matthew Hendrickson

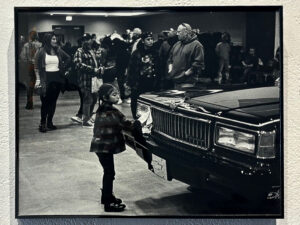

March 17, 2009 – Chicago children continue to be harmed by lead poisoning because of several glaring bureaucratic missteps — from kids being screened late to frustrated inspectors not having correct street addresses when tracking down those most at risk.

Experts say early screening is critical to catching lead-poisoning cases, but children in Illinois are not required to have a blood test until they enroll in school. By that time, some kids have already been affected.

“The problem is that this is an invisible disease,” said Tony Amato, supervisor of the city’s childhood lead-poisoning protection program. “You don’t see the effects until it is too late.”

When lead exposure goes unchecked, the toxic metal can build up in a child’s body, causing learning disabilities or worse.

“Even a point or two drop in I.Q. can be a very big deal,” Amato said.

Ideally, he said, he would like to see children screened at age 1 and each year afterward.

When children do get screened, blood samples are frequently sent to out-of-state labs for testing. If the results are positive, the labs do not always supply city inspectors detailed information to track down the kids and pinpoint whether lead paint or some other source is causing the problem.

Sometimes inspectors receive only an address for an apartment building with more than two dozen units. Other times the address might be for a relative, or the child might have a different last name than the mother.

Inspectors say testing facilities should carefully record parents’ names and phone numbers.

Even when inspectors find a lead-poisoned child and the source of exposure, regulations make it difficult for them to thoroughly address the problem. Inspectors can force building owners to only fix the apartment where the child is living, even if other units have high levels of lead, too.

Authorities also bemoan the lack of money. Chicago has just three full-time lead inspectors.

“The more money you have, the more [inspectors] you can put on the street, and the more people get covered,” Amato said.

Be First to Comment