Story by Albert Corvera

Part Two: ChicagoTalks’ urban affairs series

May 27, 2009 – Seventeen years is the average amount of time it takes for an immigrant to legally come and live in the United States. For some, it’s 17 years too long.

Louis, who didn’t want his last name revealed because of an expired green card, came to the states 14 years ago with his brother Mark from Manila in the Philippines. When he arrived at O’Hare Airport, the first person to see him was his father. Louis, then 17, hadn’t seen his father in ten years and didn’t know whether to shake his hand or hug him.

“We had been separated for so long and I didn’t know how to say hello to him,” Louis said. “It took us about a couple years to get to know who our father is.”

Louis, now 31, lived with his father while becoming acclimated to life in America. Louis’ mother stayed in the Philippines because his parents had briefly separated at the time. Today, both of his parents are once again together living in a Chicago suburb. He recalled that he and his father formed a better adult-to-adult relationship once he finished college at the Illinois Institute of Art in Chicago.

Some families, like Louis and his brother, get the luxuries and joys of reuniting with their loved ones. But others may not be as fortunate. Many apply to become citizens. And yet many still wait.

“The 17 years to wait is just too long,” Louis said. “Distance with your family is tragic. These are lost years which, hopefully, you can get back once you are settled here.”

Illinois has the eighth highest illegal immigrant population in the country. The 2000 U.S. Census revealed there were nearly 30,000 Filipinos living in Chicago.

Many Filipinos come to the states as tourists, migrant workers and as students. But once their visas expire, it’s time to return home. Those who stay, are here illegally. Many of them hide from the Immigration and Naturalization Services and become T.N.T., a Filipino term that means “in the hiding.” According to Jerry Clarito, founder and executive director of the Alliance of Filipinos for Immigrant Rights and Empowerment (AFIRE), over 280,000 undocumented Filipinos are living in the U.S. today.

The issue of immigration reform is one of the biggest obstacles facing many immigrants. Anna Guevarra, an assistant professor of sociology and gender and women’s studies at the University of Illinois at Chicago, said that now is the right time to push for reform legislation.

“We have a good administration but we really need to push for the Dream Act and get the students who are really committed but who don’t really have the path to do that,” she said. “There are a lot of undocumented Filipinos that are here to work, as are many immigrants. So if they are given the resources and the pathway to citizenship and permanent residency they can really do the work they want to do and contribute to our economy.”

The Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors Act (DREAM) is legislation reintroduced in congress by Sen. Richard Durbin (D-Ill.) and others. It would help children who were brought into this country as undocumented immigrants. The act would give these children every opportunity and right to a higher education. Students would also be given in-state tuition.

Leo, who did not want his real name used, immigrated to the states with his parents and his sister over three years ago. So far, they say they have lived good lives, have gone to school and made plenty of friends in the process. Leo’s sister Amanda, 21, finished nursing school and is currently working as a nurse on the North Side of Chicago. But Amanda could no longer be a dependent under her mother’s working visa once she turned 21. This also prevents her from renewing an Illinois Driver’s License.

Amanda, who also asked to have her name changed, could now face possible deportation because she is out of status. Right now her options are to go back to school on a student visa, get married or go back home to her native hometown Cebu, in the Philippines’ Visayas province.

Like Amanda, Leo could be facing possible deportation. At 19, Leo is still considered underage and a dependent covered by his mother’s working visa until it expires next year. As a student, Leo and his family didn’t want to apply for a student visa because tuition rates for international students are about six times higher than native students, he said.

“It’s so expensive to be an international student,” he said. “That’s one of the reasons why I didn’t want one. Also students with student visas have to go back home once they finish school. That’s not what I want to do. I love it here.”

Like his sister, Leo has limited ways of staying here. For him, it’s marriage, military or deportation. “I am willing to do anything and everything to stay here,” he said. “I love life here in Chicago. I love the people, the diversity.”

AFIRE executive director Clarito is the son of Filipino immigrants. He recalled his own immigration experience.

“At that time, my father was already a U.S. citizen,” he said. “So I came here as a legal permanent resident until I became a U.S. citizen. So I know the experiences of people waiting from the Philippines to be connected with their family. That is one of the reasons we are fighting for a change in legislation because there is about 17 years of waiting for families to get together.”

Part of AFIRE’s mission is to build the capacity of Filipino Americans community to defend constructive social change through popular education, Clarito said.

AFIRE Chicago is about immigration and their goal is to work for the reform of the immigrant Filipino community. Many of the undocumented workers in the U.S. have been waiting for a long time. AFIRE Chicago aims to protect immigrant rights as working people.

Guevarra said that many Filipinos who do come to the states end up working in jobs for which they are overqualified. In other words, she believes that many Filipinos are underemployed.

“So many of them are being funneled into low wage jobs because that is the only opportunity being given to them,” Guevarra said. “And many of them are highly skilled professionals who are teachers, doctors and nurses. However, because they are out of status they’re not able to tap into their skills.”

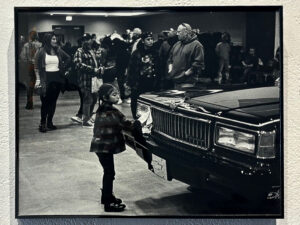

Circa-Pintig, a Filipino cultural theater group in Chicago has been highly involved in immigration rights among Filipino Americans in the community. Circa, which stands for Center for Immigrant Resources and Community Arts, gives immigrants the opportunity to be here according to membership director Levi Aliposa.

“We use the arts as a powerful tool reflecting the collective experiences, struggles and dreams of immigrant communities in America. Immigrants need to know how to feel safe so they can come out of the shadows.”

Louis, who is also a member of Circa-Pintig, said that the group only has a few American-born members. Most are first generation. The group has also put together a number of plays that dealt with immigration issues.

“There are a lot of stories within our own membership,” he said. “The immigration issue is something present with us.”

When discussing the views on the U.S. immigration issue, Clarito likens them to Matthew 15:40, a Bible parable about the sheep and the goats. The verse reads, ‘When I was thirsty, you gave me drink, when I was hungry, you fed me.’

“Jesus says, ‘whatever you do to the least of my brethren, you do unto me,’” Clarito said. “That is the connection of the parables in the Bible. We usually don’t think of the undocumented or the people who are oppressed. Jesus says that you have to do something for them.”

“We need to show the immigrants who come here to not be afraid,” said Clarito. “They are righteous people. The earth does not belong to us, it belongs to God.”

Be First to Comment